Drawing Heat

On our uncanny and changing relationship to the sun

What does it feel like to live inside the urban heat island? To be shape-shifted by the sun, whose intensity alters how we move, how we feel, what we do, where we go, how we clothe ourselves and cover our eyes and skin?

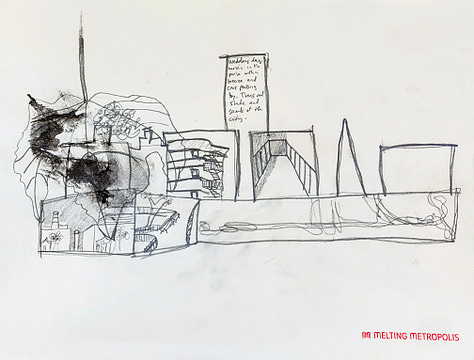

These are some of the questions that have inspired a new walkshop I have been developing in New York. An extension of ‘wild drawing’, which I think of as a tool for researching human-nature relationships, Drawing Heat has been a collaboration with environmental historians interested in the Urban Heat Island effect, who are looking to the past in order to better understand how and why we have built the sun’s heat into our cities. The project is called Melting Metropolis and involves a group of historians, geographers and community partners, with whom I am collaborating as the project’s research artist. I am following their investigations over a six year period as I develop creative ways to articulate the stories they are unearthing and co-creating.

This collaboration has led me to become ever-more curious about the sensorial and emotional nature of our relationship to the sun. Whether perceived as a sacred force or a serotonin fix, humans have long worshipped this vast spinning ball of gas, desiring and seeking out ways to bask in the light of its rays. It is the hot heart of our solar system, shaping the nature of life on Earth, from our own internal circadian rhythms to the currents of oceans, the patterns of weather and the changing of seasons. No wonder that we have lived in awe of the energies of light and heat radiating from this celestial being for thousands of years.

And yet, we all now know that the sun can harm us. We have learned to slather our skin with sun block, to shield our eyes with glasses, to cover our bodies with parasols, block perspiration with deodorant, all the while burning the remains of prehistoric organisms to fuel the excesses of our modern world and further trapping the sun’s rays within our atmosphere through the design of our cities. What else can the sun do here, other than ricochet around landscapes of concrete and glass with an intensity that we are not evolved to withstand? This new closeness is dangerous to our bodies. In the blink of an eye (relative to the sun’s 4.5 billion years and our mere 300,000 years of existence) our relationship to the sun has distorted through our preventing its escape, and no where else is this felt more than in the metropolis. Indeed, in America, heat is the deadliest natural disaster, and the intensity of heat waves is growing.

It has been fascinating walking the streets of New York this year with urban and environmental historian Dr Kara Schlichting. We both have an interest in the sensory experience of environment and, in our own ways, are thinking about how to illuminate the intimate and immersive nature of heatscapes; how our human bodies are constantly shaped and shifted by weather.

(Our bodies are) “only one of a host of entities through which heat flows and… not in any sense independent of these wider-ranging and dynamic relations.”

- Elspeth Oppermann and Gordon Walker, “Immersed in Thermal Flows: Heat as a Productive of and Produced by Social Practices,” Social Practices and Dynamic Non-Humans, ed. Cecily Maller and Yolande Strengers, 2019

Dr Schlichting’s knowledge of the urbanisation of New York is absolutely incredible. Honestly, I’ve come to the conclusion that what she doesn’t know about this city isn’t worth knowing!

One of the main things that working with her has opened my eyes to is the reality that those who were in charge of New York’s design as far back as the 19th century! were all too aware that they were building cities that would unnaturally increase temperature. Of course, they couldn’t have foreseen the impact of fossil fuels upon our atmosphere today, but it was known then that purely in terms of the geometry of the cityscape, thermal comfort would be for the privileged few. And so, much like other cities around the world, New York finds itself enclosing the sun’s rays with skyscrapers of steel and glass and landscapes of brick, stone and concrete that overlook many a-treeless street and push out hot air through ever-multiplying ACs. All the while human bodies buckle under the physical strain, our mental health deteriorating at the same time. Our cities are absolutely perfect at holding the sun’s heat close.

Together, Kara and I have been thinking about past and present experiences of heatscapes in public and private realms, and pondering over the challenge of talking about something that we cannot point to directly or hold.

“Heat is a riddle. It is largely invisible beyond its impact on bodies and things. It is intangible, but it can be felt.” - Dr Kara Schlichting

This is where drawing comes in. I’ve been curious about how I can modify wild drawing into a new practice that draws our attention closer to the invisible force of heat, while also illuminating the experiences of previous urbanites and the past decisions of those in power to build spaces that are now fast becoming unliveable.

Drawing Heat

Earlier this summer, Kara and I piloted six ‘art x history’ walks around Brooklyn, Queens and Manhattan, which we called Drawing Heat. They were programmed as part of the Asia Society’s COAL+ICE season, which focused on ways to visualise the causes and consequences of the climate crisis.

There is something about drawing while listening that I find really helps ‘land’ the information a little more deeply in mind and memory. New dots are somehow joined. Rather than passively consuming information from an external source, the act of drawing engages the body in exploring the information spatially and physically. Therefore, my intention behind Drawing Heat was to use mark-making to help groups engage more deeply with Kara’s guided history of New York, drawing attention to the present in an embodied way and sparking memories of summers past for discussion.

Truthfully, I started writing this post way back when I was in my studio in Flushing, Queens NY. It was a cool May morning, the sun was still rising somewhere through the haze, and I was surrounded by pots of inks, papers of different opacities, graphite pencils, chalk, wax crayons and magnifying glasses. Man, that was a gloriously messy, creative space! In the intervening time I have relocated back to the UK, hence pausing on posting for a while…

But now I am landed back in the UK after presenting Drawing Heat to the World Congress of Environmental History in Finland, during which I reflected on this experiment of interdisciplinary collaboration. The walkshops weren’t perfect - trying to bring the serenity of wild drawing into the hot concrete streets of New York was a very real challenge - but they did lead to some fascinating insights and conversations. And imperfection is part and parcel of research and experimentation. I thought I’d share some of the highlights from my presentation here.

Starting with the body

I believe that meaningful transformation occurs inside first and I am always looking for ways to explore how our inner worlds (and the stories we hold there) shape our outer world. Therefore, I designed Drawing Heat to explore how knowledge (about climate change) feels in our bodies. I wanted the activities to help locate where the knowledge we share as a group resonates or jars with individual experiences, follow how different stories move through our bodies, and how they move us as we travel through the outer world.

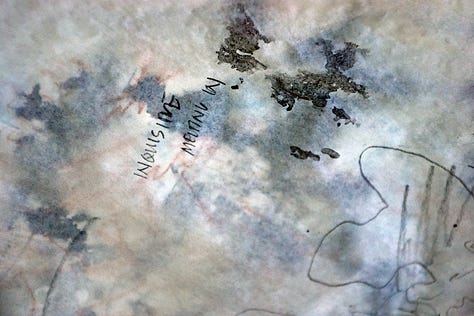

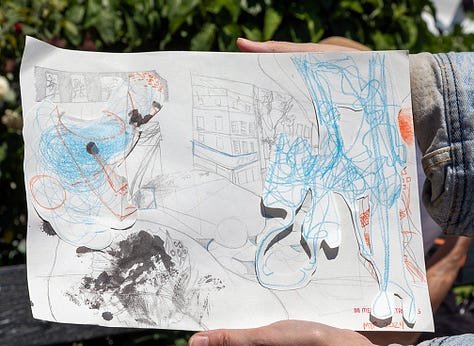

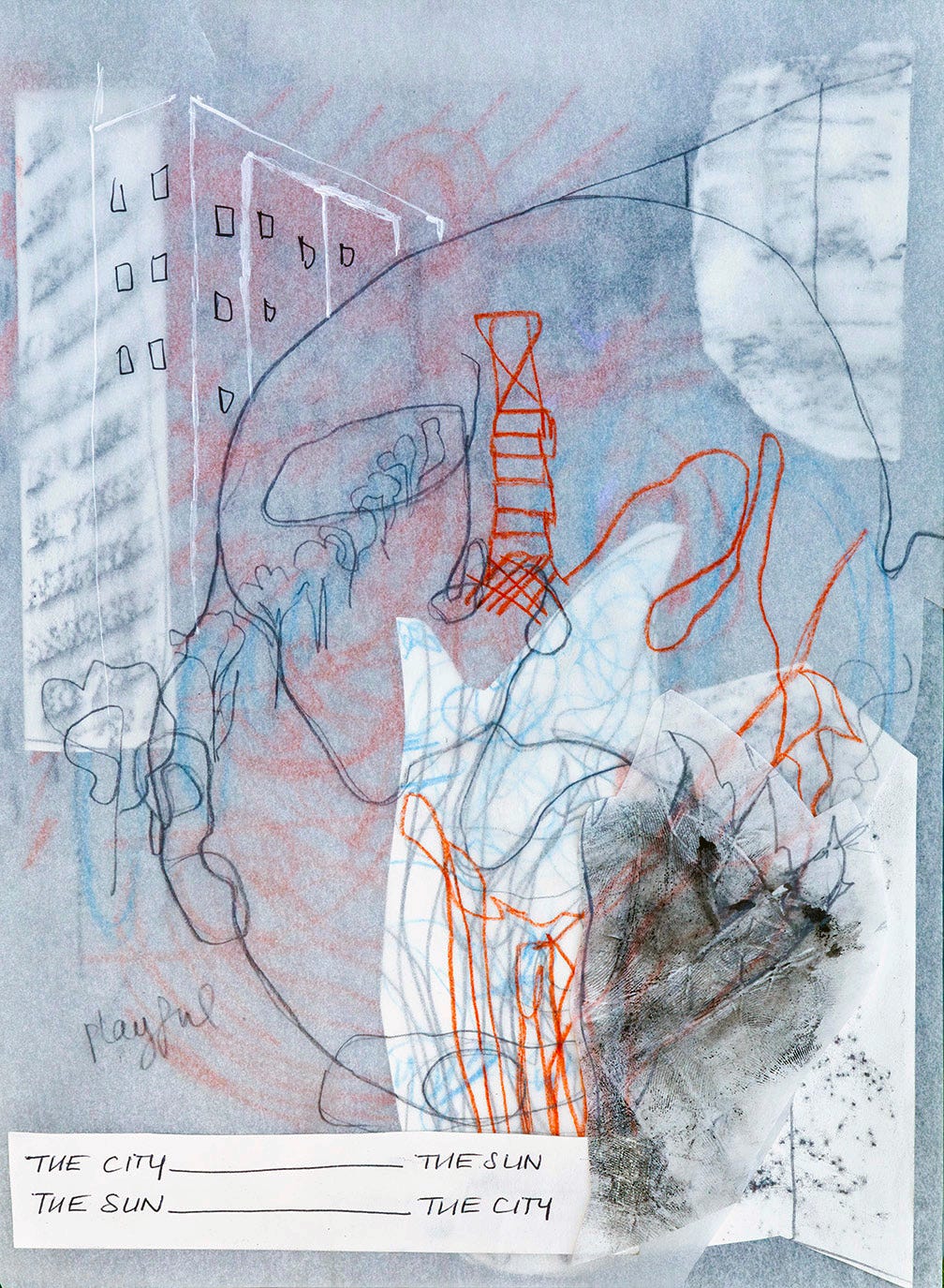

These guided walks became a kind of interdisciplinary dance between present experiences of heat (through art), and past insights anchored by place and landmarks, which required us to activate our imaginations inspired by archival sources and historical storytelling. Kara shared her observations as an environmental historian while walking through, for example, tenement buildings or a city park, and I would guide participants to draw the layers of history she had described before bringing their attention to personal memories that might be sparked by this perspective, or new information that they are receiving in that moment through their sensing bodies - sound, touch, sight or smell. The intention was that this back and forth helped build a more nuanced picture of the emergence and impact of urban heat islands for participants; the final artworks they created were composed of many layers and contained multiple perspectives of something that is by its very nature is temporal and invisible. I guess that this first iteration of Drawing Heat was my wondering out-loud about how many ways we can follow the journey of heat in our cities through time and space, by occupying different stances and studying different scales.

To provide some detailed examples, while Kara described how the material composition of cities traps heat, we took rubbings of the different surfaces and used touch to observe the different thermal qualities of our landscape. As she talked us through how particular geometries of cities create urban heat islands, we used mark-making to trace the sun’s movement through the streets, noticing whether there was a breeze, the density of humidity, the appearance of short or long shadows.

Turning to the 19th century landscape designer behind Central Park, Frederick Law Olmsted, who once described the function of parks as ‘lungs of the city… providing foliage to ‘purify and regenerate the atmosphere, in the same way as the lungs give it to blood, changing its venous blue to an arterial scarlet’’ (New York Mirror 23 July 1842), our activities also considered the city as a body and our bodies as a landscape. Through abstract mark-making and magnifying glasses we studied our own pores, which help us to perspire, comparing them to the pores of leaves that cleanse the air, and experimented with expressive lines to represent our ability to breathe when surrounded by hot air, blasted by ACs or seeking cover under trees. We also chalked the shadows of tree canopies to highlight similarities between bronchi and branches.

Latterly, we anthropomorphised the sun. I was inspired by a 19th century newspaper cartoon Kara shared, which depicted the sun as a character looming over melting buildings. These activities sparked discussions about the dynamic of the sun’s relationship to the city, and vice versa. I encouraged groups to wonder at whether it is a loving relationship, or has it become toxic? Who changed, when? Is one more to blame for the relationship breakdown than the other? Of course, these were lighthearted musings but they brought in a sense of playfulness when discussing something that can be deeply disturbing when one looks at it directly for a long time, and it provided the opportunity to reflect on our own changing relationship to the sun. Can we ever find our way back to a more harmonious connection?

As with all of my wild drawing walks, Drawing Heat ended with wide-ranging discussions about the human-nature themes that particularly resonated with the group. We also spent a great deal of time reflecting on the reality of urban heat islands as a man-made disaster and the climate injustice that has been built into our cities’ design. Maps showing how access to green and blue spaces is distributed starkly illustrated the inequity. I also found it intriguing to hear participant’s memories of summers past that were evoked by exploring the city in this embodied way - the dots that were unexpectedly joined through the act of simple mark-making or the memory traces that were happened upon while walking with a guide who looks to the past.

The experience may not have been as soothing or playful as wild drawing, but Drawing Heat certainly confirmed for me that there is further creative research to be done in searching for more nuanced, temporal and spatial ways of understanding and expressing our rapidly changing relationship with the sun. It also confirmed for me that drawing is an accessible medium through which to encourage intuitively and sensorial engagement with nature. I think the challenge I am grappling with with Drawing Heat is simply that this topic is more unsettling and the landscapes harsher than those I’ve previously explored with wild drawing. But I find this creative challenge fascinating, and now that I am back in the UK I am excited to get back into the studio to revisit the drawings we created in New York and experiment further with Melting Metropolis as their research continues.

More from me on this soon!

In the meantime, find out more about Melting Metropolis here and, if you are interested in viewing some of the historical sources we used, browse our ongoing mapping project with Urban Archive here.

Wishing you all a cool summer,

B

Loved this. You have made me think a lot about the tension between focusing on the positive and joy (wild drawing) vs bringing attention to the damage (heat drawing), and how they are both powerful and important. Finding the balance between the two perspectives is so tough in our work! Or maybe that is the work!

Amazing work. I really enjoyed this detailed reflection. How did you get involved with the research in this way?