Onto a Vast Plain

You are not surprised at the force of the storm—

you have seen it growing.

The trees flee. Their flight

sets the boulevards streaming. And you know:

he whom they flee is the one

you move toward. All your senses

sing him, as you stand at the window.The weeks stood still in summer.

The trees’ blood rose. Now you feel

it wants to sink back

into the source of everything. You thought

you could trust that power

when you plucked the fruit:

now it becomes a riddle again

and you again a stranger.Summer was like your house: you know

where each thing stood.

Now you must go out into your heart

as onto a vast plain. Now

the immense loneliness begins.The days go numb, the wind

sucks the world from your senses like withered leaves.Through the empty branches the sky remains.

It is what you have.

Be earth now, and evensong.

Be the ground lying under that sky.

Be modest now, like a thing

ripened until it is real,

so that he who began it all

can feel you when he reaches for you.— Rainer Maria Rilke (1875 - 1926)

I am cushioning this post in-between two poems that I think speak beautifully on grief and transformation, life-cycles and belonging, stillness and rebirth - held by and found within the natural world. I hope that they speak to you, too. To me, they represent the emergence of my wild drawing practice during a period of upheaval - personally, and also collectively, as we were all in the midst of the global pandemic.

In the UK, a new book has just been published called Wild Service: Why Nature Needs You, in which I have contributed a chapter on this experience of developing wild drawing. My chapter is titled ‘Belonging’ and shares how drawing became a useful tool for me to process the loss and disconnection I felt at that time, following the passing of both of my parents within a space of five months.

While I am a little uncomfortable for various reasons about the amount of times I am talking about my personal bereavements in public (and writing this chapter felt particularly vulnerable) I am doing so as a way to explain the impetus of my artistic practice as it currently stands. In truth, I cannot overstate the impact that witnessing both of their illnesses, passings, and funerals in such close proximity to one another had on my psyche and therefore, naturally, my creativity. Those experiences uprooted any sense I had had of feeling anchored, and utterly shattered the narrow certainties I had held about the human body. They starkly revealed the lack of ritual or ceremony available to those of us who are not religious, and drew me ever closer to the natural world as I returned their bodies to the earth and found solace walking (and drawing) through landscapes they had known and loved.

And so in my chapter in Wild Service we travel between Trinidad and Tobago, the homeland of my father, and rural Kent, where I grew up with my mother. Along the way, I reflect on experiences as a mixed-race child growing up in Britain and the brittleness of our understanding of belonging within the current political context. I write on the messy, unexpected emergence of wild drawing, how this led me to the point of happening across embodied ecology as a concept, and the ways in which I am exploring it with artists, academics and activists today.

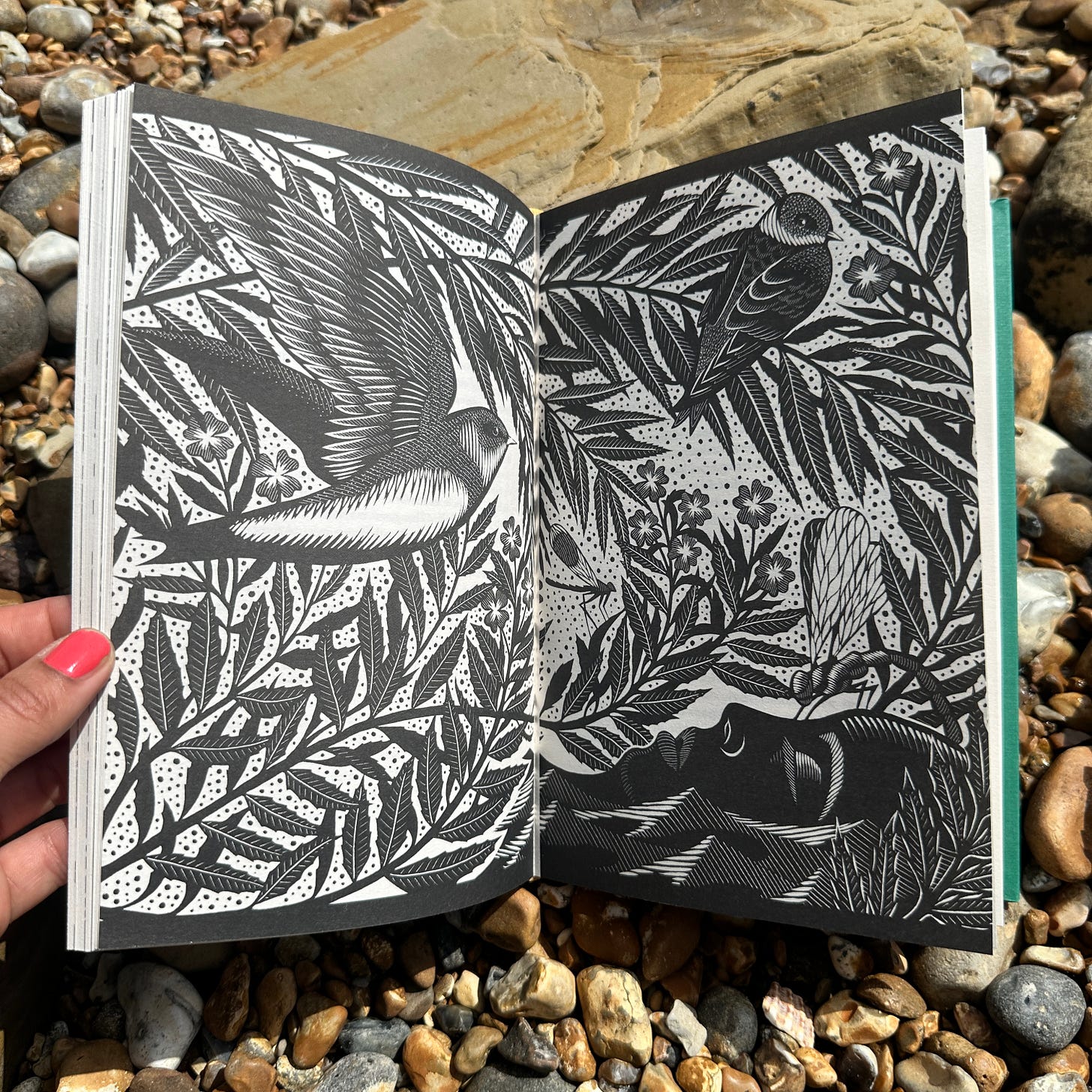

Instead of describing the chapter in full, I thought I would share a few excerpts here. (Hoping, of course, that this might intrigue you to read the full book. Please do note, as you read, the book’s utterly gorgeous illustrations created by Nick Hayes.)

On arriving in Trinidad and Tobago:

“ This was the homeland of my father. It had been decades since he had stepped foot on the island but the memories had stayed to old age, imprinted from childhood. He had often talked of his wish to show me this landscape and ever since I had learned the words ‘Trinidad and Tobago’, I had dreamed of this day. But now, finally standing on ancestral ground as an adult, the scene before me was discombobulating, saturated with sounds and shapes I did not know. I felt dizzy, and alone. . .

Eventually I reached a small clearing and looking up, swinging unsteady on the spot, I staggered. I had never seen such a tree as this in my life. Her crown must have been at least 150 feet high with branches circling the forest, wide and open like an umbrella. Armies of spiked cones traveled across her trunk, studding the spines of enormous roots that ribboned around me, almost as tall as a man. Along her lower branches streamers of feathered vines and flowers clung just out of reach.

A short, spontaneous laugh of delight burst from me; the first in a long time. She was magnificent! What had she witnessed from such a height, at such an age? This tree must have been hundreds of years old, surely unperturbed by the comings and goings of small human beings and our short, chaotic lives. A thought crossed my mind, and lingered. Had my ancestors known this tree? Momentarily disorientated by the strange sensation of past meeting present, I sat down and leant against one of the roots, careful to find a smooth section of bark.”

I then describe experimenting in the rainforest with some of the art materials I had with me. Here, I explore drawing sound:

“Moving around the page, I orientated the sounds in relation to where I was sitting, faltering at first as I struggled to quieten the judgemental chatter of my mind. Soon I picked out high pitched chirps behind me and these became light curls at the bottom of the page. A falling branch to my right turned into a heavy scribble along the edge. Songs began to twirl around the top of the sheet, following notes as they lifted before stopping abruptly and then beginning again. I became aware of their distant replies - faint strokes - and in close proximity, cicadas ticked with dashes and dots. As the sounds resonated throughout the forest, my focus began to expand further outwards. This felt good. Gradually more creatures resumed their conversations; frogs commenced their croaking - hooped marks hopping in one corner where they met soft coos - undulating lead swirls. As my ears attuned to the chorus of songs and scuttlings, a soundscape of intertwining shapes began to layer across the page.”

Reflecting on the experiences of drawing sound, touch, smell, light, shadow, motion:

“The artist Paul Klee once said that "a line is a dot that went for a walk” and that was exactly what it felt like I was doing. Just a few hours ago my whole being had felt condensed to a tiny dark point, a shocked to stillness clay-body retreating from the human world. Here now, though, it felt like the act of drawing was playfully guiding me out into the vastness of the more-than-human world, calling my attention to the myriad life forms that tumbled and glided and scurried around me. Or rather, alongside me. . .

The sensation felt almost like space was expanding around me, creating room into which it was safe to not only unfurl my grief but also connect with the sheer beauty, wonder and (dare I say it?) joy of being alive. Gratitude awakened in me there, grounding my body into what lay beyond the barrier of my skin, the present moment evolving into a new experience of presence.

This wasn’t some kind of sublime out-of-body spiritual experience - it was visceral. Beetles tickled my knees, nesting birds shat on my rucksack, mosquitos guzzled my blood. Spiked prongs scratched my shins, the sun prickled my skin and beads of sweat rolled down my face. This new felt awareness was as messy as it was glorious.”

On turning this practice into guided walks:

“Guiding wild drawing walks through the city challenged my own notion of nature as being something “out there”. With magnifying glasses we studied the minute worlds within worlds of lichen curving around grooves of tree bark, woodlice clambering over mossy tops, spider webs tugged by gusts of wind, drops of ink spooling into rain spots on our page. These experiences deepened my sense of always being in nature. Wind, rain, sun and earth, moths, beetles, crows, and dandelions; nature pushed through the cracks of city walls and filled our skies. Coupled with the embodied quality of this practice - touching, listening, tasting, smelling and observing the natural world - wild drawing was not only renewing my relationship to nature, but also to myself.”

And finally, on landing upon the central question in my artistic practice today:

“In the West, so much of what we learn about nature comes from narratives that treat it as something ‘other’, to be tamed, controlled, feared, extracted and owned. I began to wonder what might happen if we instead engaged with an embodied clarity of ourselves as humus; as organic beings temporarily animated as human, destined to reintegrate into the living world that our human systems are rapidly degrading. If we cultivated an understanding of our very beingness as land, surely this would reveal the impossibility of our not belonging and in so doing perhaps transform our relationship to the nature crisis and the systems that perpetuate it?”

Engaging with the natural world through the arts has played such a vital role in renewing my sense of belonging and I am grateful to wild drawing for its gentle nudging me towards broader, more nourishing understandings of myself as a member of a rich, dynamic natural world. Drawing for me came from a real sense of absence and loss, but now it is my daily source of little moments of joy, presence and awe, and my own small act of Wild Service. Writing the chapter for me was essentially a releasing of ludicrous human-definitions of who gets to belong where, and a meditation on our eventual return to where we came from: earth, soil, humus.

In May 2022, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences released a paper that measured fourteen European countries on three factors: biodiversity, wellbeing, and nature connectedness. Britain came last in every single category. And so the findings are clear. We are suffering, and nature is too.

Wild Service: Why Nature Needs You is a concept crafted by the pioneers of the Right to Roam campaign, which argues that humanity's loss and nature's need are two sides of the same story. Blending science, nature writing and indigenous philosophy, the book calls for mass reconnection to the land and a commitment to its restoration. Alongside my chapter on Belonging, other activists and artists write on themes such as Reciprocity, Kinship, Guardianship, Education and Recommoning.

I am honoured to have contributed to a book filled with powerful and beautiful stories of how we can reconnect to the land. But don’t take my word for it. Here is Patrick Barkham’s review in the Guardian:

“Powerful . . . [Wild Service] is a call to action that might just be the founding text for a new environmentalism. A forthcoming book by a diverse band of right to roam campaigners offers a radical new vision of how people can repair both the natural world and their broken relationship to it.”

As ever, please do share any reflections you have in the comments below - on the poems, these excerpts or indeed, the book itself. It’s available now in hardback and, if you’re buying a copy, may I gently encourage you to purchase from an independent retailer or directly from Bloomsbury? (#boycotAmazon)

With love,

Bryony Ella

The Wild Iris

At the end of my suffering

there was a door.

Hear me out: that which you call death

I remember.

Overhead, noises, branches of the pine shifting.

Then nothing. The weak sun

flickered over the dry surface.

It is terrible to survive

as consciousness

buried in the dark earth.

Then it was over: that which you fear, being

a soul and unable

to speak, ending abruptly, the stiff earth

bending a little. And what I took to be

birds darting in low shrubs.

You who do not remember

passage from the other world

I tell you I could speak again: whatever

returns from oblivion returns

to find a voice:

from the center of my life came

a great fountain, deep blue

shadows on azure sea water.— Louise Glück (1943 - 2023)

Oh wow, having previously not read it, this is the 2nd time this week I've been led to Louise Gluck beautiful The Wild Iris poem and it speaks to me of hope for freedom and rebirth from my own dark space deep within Earth's bowels. Chronic illness (and all that encompasses) cloaked in pre-menopausal drama & lethargy has me buried but I do sense those birds flitting around like fireflies in the night. Incidentally, I just realised my partner, unbidden, brought me a stunning iris from the garden yesterday, so it's definitely a sign / synchronicity..

Thank you for sharing the poems and some of your embodied ecology thinking and wild walk processes. I'm so sorry for the terrible loss you suffered, I can't begin to imagine.. and I'm delighted you have discovered such a nurturing way of coping through art & nature. That's beautiful. And the sharing is pure poetry, thank you.

The book and your chapter sound wonderfully essential (though I will wait patiently for the paperback version - arthritic hands don't cope well with stiff book spines!). Thanks again x

Dear Bryony, this is a good piece. Can I translate part of this article into Spanish with links to you, and a description of you, this book and your newsletter?